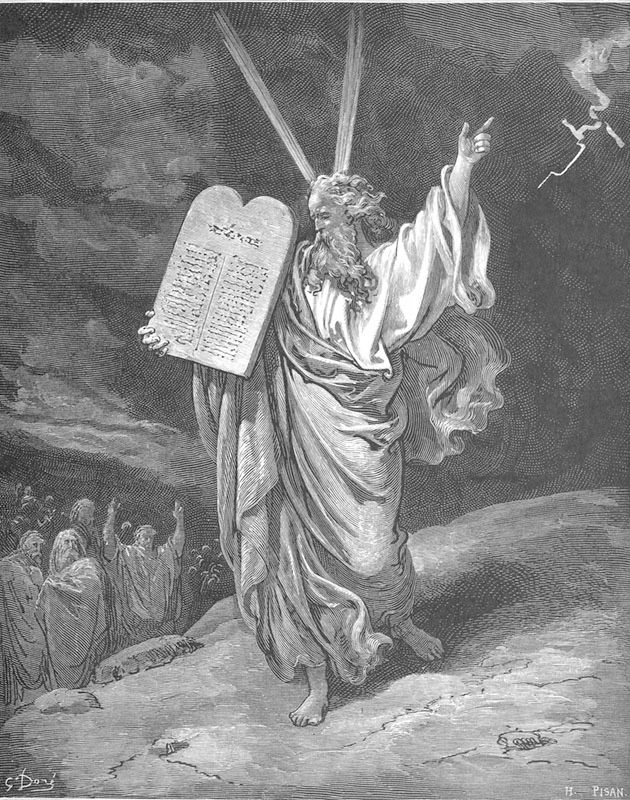

The Prophets were expecting another redemption and a time when Torah would be written on hearts rather than stone

The article below is based on this sermon preached at Christ Our Redeemer Anglican Church in Oklahoma City on the Fifth Sunday in Lent, Passion Sunday.

31 “Behold, the days are coming, declares the Lord, when I will make a new covenant with the house of Israel and the house of Judah,

32 not like the covenant that I made with their fathers on the day when I took them by the hand to bring them out of the land of Egypt, my covenant that they broke, though I was their husband, declares the Lord.

33 For this is the covenant that I will make with the house of Israel after those days, declares the Lord: I will put my law within them, and I will write it on their hearts. And I will be their God, and they shall be my people.

34 And no longer shall each one teach his neighbor and each his brother, saying, ‘Know the Lord,’ for they shall all know me, from the least of them to the greatest, declares the Lord. For I will forgive their iniquity, and I will remember their sin no more.” (Jeremiah 31:31-34)

Jeremiah was one of the last voices warning the Kingdom of Judah that judgment was coming. The Israelites repeatedly were unfaithful to God, breaking vows they made at the time of Moses.

In the first Exodus, God freed Israel from slavery in Egypt and whisked them away into the wilderness. At Mount Sinai, God and Israel promised to be faithful to one another as in a marriage relationship.

But Israel became a wayward spouse and worshipped other gods and failed to care for the most vulnerable in society. God was patient for more than 400 years. But enough was enough. God enacted the judgment clauses of the nuptial agreement (the Torah) and sent Babylon to judge Israel. The people were forcibly removed from the Promised Land.

But even as God pronounced judgment through Jeremiah, God offered comfort. When God judges, he always offers comfort and he always makes a way for restoration.

In Jeremiah 31, God restates his commitment to Israel. God promises to make a new covenant with the 12 tribes of Israel. This new covenant will differ from the Mosaic covenant, not necessarily in content but in execution. The content is still the Law. Law – that’s such a heavy word. When you read Law in the Scriptures, think Torah, think Community Instruction. The Torah is God’s guide to how we are to relate to him and to each other.

In his New Covenant with Israel, God promises to

- “put my law within them, and I will write it on their hearts.” Torah, God’s community instruction, will no longer be external to be learned in a human way. It will instead be internally recorded and taught by the Holy Spirit. God will write it on their hearts.

- “be their God, and they shall be my people.” This is the same as in the Mosaic Covenant. God promises to make Israel his treasured people. Israel’s part is to make God their treasured life partner.

- “No longer shall each one teach his neighbor and each his brother, saying, ‘Know the Lord,’ for they shall all know me, from the least of them to the greatest, declares the Lord.” This is a promise of a personal relationship with God for everyone, no matter your social status, your financial status, your educational status, your marriage status, your health status. Every Israelite in the New Covenant will know God personally.

- “I will forgive their iniquity, and I will remember their sin no more.” In the New Covenant, God promises to forgive and forget the sins of his people, the infidelity to him and to each other.

To whom are these promises of a New Covenant made? To Israel and Judah. To the 12 tribes of Jacob.

Has God kept this promise of a New Covenant? When and how?

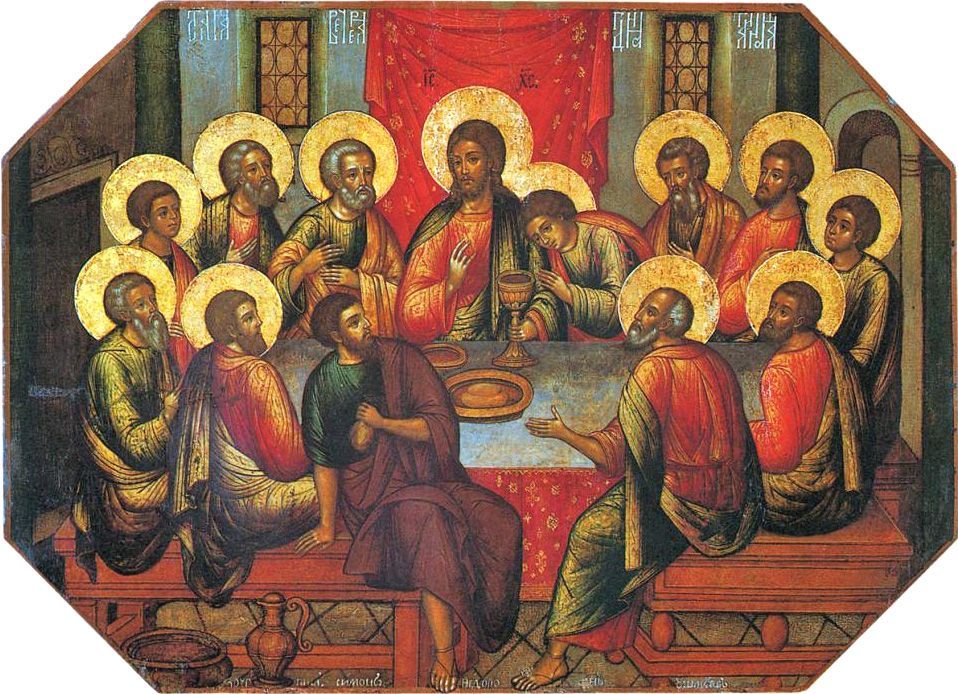

We call the “Christian” half of the Bible the New Testament or New Covenant. If you’ve ever wondered why, the answer is Jeremiah 31 and Luke 22.

1 Now the feast of Unleavened Bread drew near, which is called the Passover.14 And when the hour came, he reclined at table, and the apostles with him.

15 And he said to them, “I have earnestly desired to eat this Passover with you before I suffer.

16 For I tell you I will not eat it until it is fulfilled in the kingdom of God.”

17 And he took a cup, and when he had given thanks he said, “Take this, and divide it among yourselves.

18 For I tell you that from now on I will not drink of the fruit of the vine until the kingdom of God comes.”

19 And he took bread, and when he had given thanks, he broke it and gave it to them, saying, “This is my body, which is given for you. Do this in remembrance of me.”

20 And likewise the cup after they had eaten, saying, “This cup that is poured out for you is the new covenant in my blood.” (Luke 22:1, 14–20)

In verse 20, Jesus says, “This cup which is poured out for you is the new covenant in my blood.” Jesus, the Word of God made flesh, pronounces the start of the New Covenant of Jeremiah 31 at the Last Supper. Or maybe we should call it the First Passover of the New Exodus. What do I mean?

We saw in Jeremiah 31 that God referenced “the covenant that I made with their fathers on the day when I took them by the hand to bring them out of the land of Egypt.” For reasons we won’t cover today, the people of Israel wound up enslaved in Egypt. They cried out for salvation, and God raised up Moses. Through Moses, God brought judgment on Egypt for their idolatry and for enslaving Israel.

God’s final judgment on Egypt would affect all those who lived there. But God made a way of protection: the Passover meal.

In Exodus 12, God told Israel how to protect themselves from the coming judgment. They were to kill a sheep or a goat, put its blood over the door, roast the lamb, and eat it with unleavened bread. All peoples – Israelite or Egyptian – in houses where this meal is eaten were saved from God’s judgment on Egypt.

God commanded that this salvation meal be remembered every year. To this day, Jewish families gather every Passover to remember how God saved them from Egypt.

In the thousands of years since the Exodus, the Passover meal has evolved. It’s always included unleavened bread (matzah), but by the time of Jesus, four cups of wine had been added as symbols of joy and God’s four promises to Israel in Exodus 6:6-7:

- I will bring you out from under the burdens of the Egyptians

- I will

deliver

you from slavery to them

- I will

redeem

you with an outstretched arm and with great acts of judgment.

- I will

take you to be my people, and I will be your God.

I recently read

The Nazarene, a novel based on the Gospels by Jewish writer Sholem Asch. It was published in 1938. Like The Chosen on TV today, The Nazarene puts Jesus back in his Jewish context and teases out details non-Jews might miss.[ii]

In the novel, Asch succeeds in giving readers a sense of the messianic expectation that arose every Passover. Was this the year God would throw off the Roman oppressors? Who in the Jewish community was with the latest revolutionary? Who was opposed to an uprising for political, financial, or religious reasons?

And what of this Jesus of Nazareth who preaches an elevated Torah in the Sermon on the Mount, who provides bread from heaven to feed the 5,000, who speaks to Moses and Elijah on the Mount of Transfiguration? Is he the Messiah? Is he the Prophet Like Moses? Is he the Son of God?

Jesus answers these questions through his actions at the Last Supper.

We see Jesus take wine twice in Luke 22. More than likely, Luke records the first and the third cup of the Passover meal. Luke next says,

19 And he took bread, and when he had given thanks, he broke it and gave it to them, saying, “This is my body, which is given for you. Do this in remembrance of me.”

With the help of Matthew’s Passover account (Matt 26:26), we know that this happened while they were eating. So Jesus paused the meal, blessed a piece of matzah and said the bread represents his body.

This is highly unusual, not just equating the bread to his body but the timing of the eating of the bread. The last thing you were supposed to eat – in Jesus’ time – at the seder was the Passover lamb. But Jesus has them eat bread last and says, “This is my body, which is given for you.”

With this action, Jesus is saying, “I am the ultimate Passover lamb.” Paul affirms this by saying Jesus is our Passover sacrificed for us (1 Cor 5:7).

Then we see Jesus take wine again after supper, Luke 22:20: “This cup which is poured out for you is the new covenant in my blood.” This is the third cup of the Passover meal, the Cup of Redemption.

With this cup of wine, Jesus announces to his Jewish disciples the arrival of New Covenant promised through Jeremiah centuries before! He is in effect saying, I am the Prophet Like Moses. This is the new exodus. I am the God who redeems you. I am writing my Torah on your heart.

When we come to the Communion table, we are partaking in a compressed Passover meal. We are remembering Jesus’ death until he comes, as he asked us to. We are also stepping into the New Covenant promised to Israel and Judah.

How can non-Jews, step into this promise? Because God chose Abraham on our behalf. The call of Abraham was always to bless the all the nations that rebelled at the Tower of Babel (Gen 10, 11). “In you,” God tells Abraham, “all the families of the earth will be blessed” (Gen 12:3).

In the New Covenant, God promises those who sign on – Jew and Gentile – that

- He will write his good instruction on our heart.

- We will be God’s people and he will be our God.

- We will have a personal relationship with God.

- Our sins will be forgiven and forgotten.

God will judge the sin of this world as he judged Egypt. Every injustice will incur God’s wrath. We are all sinners. We have all been unjust. We all deserve God’s wrath.

But he has made a way of forgiveness, of protection, of redemption. We need only take on the blood of Jesus, the ultimate Passover lamb, upon the door of our hearts. We need only come to the Communion table at his invitation and celebrate his victory over sin and death by eating his bread and drinking his wine.

Footnotes

i. A. Chadwick Thornhill, “Exodus,” The Lexham Bible Dictionary (Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2016).

ii While the retelling of the Gospel account in The Nazarene is fairly faithful to the biblical account, the author Sholem Asch seemed to believe that Jesus is the Messiah for the Gentiles only, words he puts into the mouth of his version of Nicodemus the Pharisee. The book is worth reading for its Jewish perspective on Jesus and its discussion of Christian antisemitism.