First Sunday in Advent - Year B

Sermon Notes from the Church’s Ministry Among Jewish People

RCL Readings – Isaiah 64:1-9; Psalm 80:1-7, 17-19; I Corinthians 1:3-9; Mark 13:24-37.

ACNA Readings – Isaiah 64:1-9; Psalm 80[:1-7]; I Corinthians 1:1-9; Mark 13:24-37.

Introduction.Advent is not a month-long shopping spree before Christmas. It is a time set aside for spiritual reflection and preparation regarding the coming of the Messiah. It’s a time of renewed commitment to prayer, deeper reading of the Scriptures, and perhaps even some fasting–all in the context of getting ready. The question then is: what are we getting ready for?

The first Sunday in Advent marks the beginning of the new liturgical year. There are many ‘New Years’. Most of us will celebrate a secular new year at the beginning of January, while the Jewish calendar marks a new year in the middle of September. Additionally, those in education will talk of the academic school year while those in business will note the financial (tax) new year. Advent, of course, provides us a time to reflect and celebrate the first coming of the Messiah. In whatever way we choose to measure our lives, new beginnings are always opportunities to reflect, but they must also be a time to make plans–and for Advent, plans for how to live as we anticipate the Messiah’s second coming. To comprehensively grasp and proclaim the Gospel, it is crucial that we embrace and affirm both of these significant events.

Common Theme. Preaching about judgment is often avoided, perhaps because it proclaims uncomfortable truths. One invaluable aspect of the lectionary is that it compels us to focus on all aspects of Scripture and not just our favourite passages from the Bible. The Scriptures before us revolve around the last judgment; however, in reflecting on judgment they remind us that God is both love and a consuming fire. In the end, all things that are wrong will be made right and, if we are being truly honest, then we acknowledge that we are not excluded from that process.

Hebraic Context. In Hebrew, the end times are usually called אחרית הימים, meaning ‘end of days’ or ‘the last days’.[1] The term first appears in Genesis 49:1 and then again in Numbers 24:14.[2] In Genesis the context is Jacob’s blessings given to his sons. Those blessings, depending on the son, include things which are both positive and negative. The context in Numbers is Balaam, the prophet who was contracted by Balak, king of Moab, to curse Israel. Instead of being able to do so, he could only bless. From the context in which the term first appears in both Genesis and Numbers, the ‘last days’ encompass both a blessing and a curse–something good and something bad. A rabbinic discussion recorded in the Talmud notes that when things start looking bad, that’s the time to look up as redemption draws near. Rabbi Johanan said: “When you see a generation overwhelmed by many troubles as by a river, await him, as it is written, ‘when the enemy shall come in like a flood, the Spirit of the Lord shall lift up a standard against him;’ which is followed by, ‘and the Redeemer shall come to Zion’” (Sanhedrin 98a). The Hebraic perspective on the last days acknowledges that there is a judgment, but believers should not be afraid. However, the faithful should also recognize the need to be alert and ready–with the potential for suffering and persecutions beforehand.

Isaiah 64:1-9. The prophet Isaiah plays a prominent role in many of our Old Testament lectionary readings for this Advent season. Historically, he was a contemporary of the prophets Micah, Amos, and Hosea and his prophetic career began following the death of King Uzziah. Isaiah’s ministry flourished during the expansion of the Assyrian empire, with Isaiah 36-37 indicating he was an eyewitness to the Assyrian siege of Jerusalem. According to Jewish tradition, recorded in the apocryphal source, The Ascension of Isaiah, he suffered martyrdom during the reign of Manasseh by being sawn in half inside a tree. The Epistle to the Hebrews (11:37) may allude to this event.

The final chapters of his extensive work prophesy everlasting deliverance and salvation as well as everlasting judgment.[3] Isaiah 64 is a prayer in which the prophet calls on the Lord to intervene from heaven. Isaiah’s name means, “The Lord is salvation”. The opening verses are a summons for the Lord to make His name known amongst the enemies of Israel. The imagery is dramatic with Isaiah pleading for the Lord to come down to earth, rending the very heavens in the process. The backdrop for the Lord’s coming (advent) is the preceding chapter 63, in which the expectant Day of Vengeance is encapsulated in the wrathful figure coming from the East stained in the blood of His enemies. While the call is for the Lord to bring judgment on the enemies of God, Isaiah admits that even Israel is not innocent nor deserving of God’s salvation. Isaiah confesses that Israel has sinned before the Lord with everyone becoming unclean. “All our righteousness is like filthy rags”.[4] In the light of the expectant coming of God and subsequent judgment, the prophet returns to a posture of humility and intercession. God is referred to as ‘Father’[5]; not as a harsh judge, and Isaiah implores Him not to abandon the ‘work of His hand’. We might be sinners deserving judgment but we are still the people of God. The final call of Isaiah is for the Lord to forgive and not remember the sins of Israel.

Psalm 80:1-7, 17-19. According to I Chronicles 6:31-32, David assigned a number of Levites to function as worship leaders in the Tabernacle and one of those men is named Asaph. While many Psalms are attributed to Asaph, it is sometimes unclear whether they are written by Asaph, Asaph’s descendents, or even his school of worship leaders.

Psalm 80 is a call for the restoration of Israel after being ravaged from some external power.[6] Asaph presents God as a shepherd who dwells between the cherubim. Which is most likely a reference to the cherubim that adorn the ark of the covenant.[7]

The image of the ruler or deity being a shepherd over the people was not uncommon in the ancient world. Shepherds were not weak, oppressed peasants in the ancient world, they were rich, often even rulers and kings. The biblical Patriarchs, many of the judges and some of the prophets were shepherds by profession. The biblical shepherd had the role of guide, provider, and defender. The Lord, as the ultimate mighty shepherd of Israel, is called upon to stir up His strength and come save His people. Three times in the Psalm there is the appeal to God to restore His face towards Israel. The Hebrew word is הֲשִׁיבֵנוּ HaShiveinu and can be read as restore, return or turn us back towards [Your face]. The term, the face of God, is embedded deep in the Aaronic blessing of Numbers 6:24-26–a blessing that the levites would regularly pronounce over the people of Israel.[8] God’s face is synonymous with His presence, blessing and favour. The desire of the psalmist is for the presence of God to return and to be once again among His people, thus bringing blessing and peace. These themes are poignant for the season of Advent as we hold fast to the hope of the blessed return of the Lord and contemplate His presence within our communities and churches.

I Corinthians 1:3-9. In this opening section of Paul’s letter to the Corinthian community, there is an obvious outpouring of thanksgiving. Paul’s gratitude is rooted in what the Messiah has done, is currently doing, and will do in the future. Paul references the numerous blessings bestowed on the Corinthian believers through the grace of God. Primarily, among these blessings is their abundance of spiritual gifts to put into practice within their community–with the promise that God will do even more when the returning Messiah is revealed.

Paul expects the Corinthians to “eagerly await” the second coming of Jesus. If we are honest with ourselves, many of us find the practice of ‘waiting’ to be somewhat challenging. In our modern culture of immediate access to information and gratification, most of us will not wait ‘eagerly’ for anything. Yet waiting is an important part of our discipleship and spiritual discipline. The early community of the disciples of Jesus began by waiting. For ten unique days, those early disciples were simply waiting in Jerusalem. They were not told exactly how long this wait would be, but they knew of the hope which was in front of them–namely, the mysterious and wonderful promise of the full baptism in–or of–the Holy Spirit (Acts 1:4-5).

This task of waiting is an important feature of the Advent season.[9] But we do not passively wait. First, there is an expectation within the waiting. God is faithful and God has always been true to His promises. God sent the Messiah, just as He promised He would, and the Messiah will return also as promised. One aspect of being a disciple of Jesus is the expectant waiting of His return. And so we should also wait faithfully. Jesus taught about active waiting and preparation through the parable of the ten virgins[10] in Matthew 25. All ten virgins waited for the bridegroom and all ten virgins slept. The parable differentiated the virgins between those who were wise and those who were foolish. What was the difference? The wise bridesmaids had prepared themselves for the delay of the bridegroom through the adequate provision of spare oil.[11]

Mark 13:24-37. In today’s Gospel passage we have the only place in Mark’s Gospel where we hear Jesus giving a long consecutive teaching on a single topic. The teaching is focused on the end of the age and both Matthew 24:1-51 and Luke 21:5-36 contain similar and complementary teaching on this important topic. The passage begins with the words ‘in those days’ which is a well known Hebraic saying linked to the end times (see Jeremiah 33:15-16, Joel 3:1 and Zechariah 8:23). In verse 26 there is a clear reference to the coming of the Son of Man which has been interpreted by many scholars as a reference to the Second Coming. However, during the Second Temple period, the title "the Son of Man" primarily drew its significance from the book of Daniel.[12] In its original context, the reference is to an eschatological character (the Son of Man) who ascends from Earth to Heaven to encounter the Ancient of Days. The character of the Son of Man in the book of Daniel appears in the context of a heavenly judgment scene. In the book of Daniel the Ancient of Days (God) presides over a seated court as books are opened. Authority to judge and to rule is handed over to the Son of Man who enters this heavenly judgment scene. The Messiah will now judge the world. When this eschatological verdict is to be given is not known. However, there is the call to learn from the metaphor of the fig tree. The leaves of the tree provide a hint as to the season.[13] On one hand there is the assertion that no one knows the timing of the Second Coming, and on the other there is the command to watch and observe the season. This implies a readiness and a high level of expectancy.

The interpretation and application of the term ‘this generation’ and ‘all these things’ (vs30) has been and is still a major area of theological debate. There are three main lines of interpretation.[14] Whichever interpretation you choose, in explaining when to repent, Rabbi Eliezer told his students to “Repent one day before your death.” His disciples asked him, “But does anyone know the day of their death?” Eliezer responded, “All the more reason to repent today.”[15] We may not know the day or the hour of judgment. But we do know that this is the season in which to recommit ourselves to watchful prayer and humble obedience. Not because of a fear of the future but because of an eager optimism through faith in the soon return of Jesus.

Hebraic Perspective. Throughout the Bible we are made aware that God can and does bring judgment on the world. During the Exodus we see God enter into judgment against the gods of Egypt. At the same time that God is a judge the book of Exodus tells us He is also a redeemer, provider, sustainer and lawgiver. Later, the prophets remind the people that for disobedience judgment looms at the hands of the living God! During the 2nd Temple period the responsibility to enact the final judgment was understood to be the task of the Messiah. The Dead Sea Scrolls community named Melchizedek as the coming messiah and spoke of a day in which he would exact judgment. The criterion for judgment is echoed in the prophets of Israel. We are judged on our care and concern for the weak members of society: the poor, the orphan and widow. Proverbs 19:17 explains that the concept of helping the poor is actually helping the Lord, and the Lord is faithful to reward. This is not biblical socialism. Being poor does not make you holy and being wealthy does not make you evil. Instead it is about imitating God’s character as followers of the Messiah.

ACNA Readings

Psalm 80:1-7, (8-16), 17-19 - Asaph uses the motif of a vine as well as sheep to represent Israel in her sacred history. Both vine and flock are not uncommon images of Israel in both the Hebrew Scriptures and the New Testament. The later portion of the psalm portrays the sovereignty of God through His dealing with the vine. First the vine (Israel) was transplanted from Egypt, where Israel had been enslaved for 430 years, to a new land. The new land is not named, though the obvious location is Canaan. The ground was prepared by God who drove out the nations that had inhabited the new land and the vine flourished. Vineyards are often protected by a surrounding wall or hedge to deter animals and potential thieves. In verse 12 the psalmist asks the Lord why He has broken the protective wall exposing the fruit of the vine to plunder? Asaph begs the Lord to see the suffering this has brought upon the people. In so doing the psalm declares how God is author of both blessing and misfortune in the history of Israel. His sovereignty is seen through all of Israel's history both the good and the bad. Israel needed a redeemer, a leader to guide them back on the path of restoration and repentance to God. Verse 17 looks for God to raise up a ‘son of man’ who will faithfully call upon the Lord and bring about the redemption of God’s people. The term ‘son of man’ here simply means a human being in its literal sense. But prophetic implication renders the term son of man with messianic aspirations.

Further reading. Mark 13:28-29: Flusser D Notley RS. The Sage from Galilee : Rediscovering Jesus' Genius. 4Th English ed. Grand Rapids Mich: William B. Eerdmans Pub; 2007. Pp 124-125

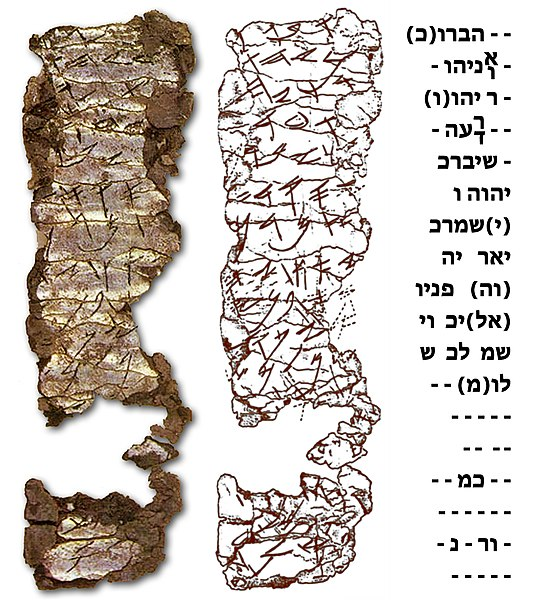

(see picture below)

A Silver Scroll with the Priestly Blessing inscribed on it. This scroll was discovered in the tombs at Ketef Hinnom, just above the Hinnom Valley, Jerusalem. Hayardeni, Tamar. 2008

(see photo below)

One of my Archaeological teachers, Gabi Barkay at Ketef Hinnom, where he discovered the Ketef Hinnom scroll in 1979.

Endnotes

- Numbers 24:14; Deuteronomy 4:30, 31:29; Jeremiah 23:20, 30:24, 48:47; Ezekiel 38:16; Hosea 3:5; Daniel 10:14; along with: Genesis 49:1; Isaiah 2:2; Jeremiah 49:39; Micah 4:1 (and Daniel 2:28)

- Both Jacob and Balaam are prophesying, one over his children and the other over the children of Israel, involving both blessings and curses. In Jewish tradition, when words first appear in the Scriptures the context will forever give a nuance to the word or term. Thus the term ‘last days’ has the nuance of a future event involving things that are good and bad at the same time.

- The subjects of death, the afterlife, heaven, and hell can be slightly hazy in the Hebrew Scriptures. The heavens (plural) are part of the original creation week and later we encounter references to a place called sheol which provides almost no detail in its relationship to heaven. The concept of heaven and hell as we understand them today in the Judeo-Christian tradition developed during the 2nd Temple period following the return from Babylonian exile. But the notions of the world to come as it relates to eschatology starts to be seen more clearly in the later prophets such as here in Isaiah.

- The Bible reveals God as not only the source of life, but as Life itself, and the people of Israel are commanded to imitate Him and reflect His character by reverencing life. Death entered the world as a result of Sin and the book of Leviticus prescribes the solution for both the moral and ritual result. These two kinds of impurity, ethical/moral sins, leading to punishment and exile, and ritual/bodily uncleanness from contact with death, leading to exclusion from God’s Presence, both require cleansing. The sacrifice on the Day of Atonement deals with sin (Lev 16). The Torah regulates impurity caused by contact with death–the dead body of a person or animal, the loss of life-giving body fluids (semen and menses), even skin diseases that makes a person appear as if they are decaying (Lev chap 11-15). Such impurity can be removed through ritual, mainly through bodily immersion, and is generally not a sin as one can become impure in the course of daily life (burials, sexual intercourse, childbirth, etc.). It was only considered sinful to remain unclean by not following the prescribed biblical ritual. But ethical or moral impurity (adultery, idolatry, murder, witchcraft, sacrificing children) cannot be dealt with by ritual–only by repentance (Psalm 53). Even the Land itself can become impure through immorality, idolatry, or bloodshed (Lev 18). Again, there is no ritual for such sins–genuine repentance is required. The prophets and psalmists often use the terms pure/clean or impure/unclean as general metaphors for good and evil but we should not forget that God even required ritual purity in order to approach Him. Isaiah cleverly combines these two forms of death in the form of ritual impurity (not sinful) and iniquity (sinful) together here in Isaiah 64:6. The New Testament continues that understanding (Matthew 15:18-20, 2 Corinthians 6:6).

- God as a father figure is not only found in the New Testament–See Deut 32:6; Isaiah 63:16; Jeremiah 3:19; Jeremiah 31:9; and Malachi 2:10. See also Exodus 4:22-23; Deuteronomy 1:31; Psalm 68:5; Psalm 103:13; Proverbs 3:12; Isaiah 66:13; and Hosea 11:1-4. The Biblical understanding of Av ‘Father’ also carries with it the concept of Patriarch, called the Avot in Hebrew. More than a biological relationship, the Avot were guardians, teachers, guides, and custodians of a people and of a people’s future. The merit of a patriarch could produce positive influence for the future generations. As Paul writes in Romans 11:28 ‘As far as the gospel is concerned, they (Israel) are enemies for your sake, but as far as election is concerned, they are loved on account (merit) of the patriarchs’.

- There is no definitive reference to the name or nature of the enemy from which the psalmist calls for rescue and restoration. Likewise, there are no references to any particular sin (or even sin in general) that we can historically trace. But even if the Psalm doesn’t speak of spiritual matters, the Psalmist still turns to God for help–perhaps something we should learn from as He is the God of both the spiritual and the physical. Regardless, there are no clear internal makers to help scholars place the time of composition of this psalm. Nonetheless, it is common to think that this is a slightly later Psalm as the Vine and Vinedresser became more popular motifs in the prophets (Isaiah, Jeremiah, and Ezekiel) of the late Kings.

- Asaph mentions three tribes here: The tribe of Benjamin and the tribes of Joseph. The Ark of the Covenant resided in each of these locations, first in Shiloh, in the tribe of Ephraim, and later in Kiriath-Jearim on the border of Benjamin. However, Manasseh is an odd inclusion in this list if this is the argument, as neither the Ark nor tabernacle resided there. Numbers 2:17-24 does speak of the three tribes directly following the tent of meeting but it doesn’t have a strong link. Asaph seems to speak of the northern tribes more than any other Psalmist – Ephraim, 78:9, 67; 80:3: Manasseh and Benjamin, 80:3: Joseph, 77:15; 78:67; 80:2; 81:5 which may be due to [his] lineage, background, or place of residence? Levitical cities were spread throughout both Judah and Israel. A rather minor northern battle is also mentioned in 83:9-10 rather than more common ones in the south.

- Amulets, such as the silver Ketef Hinnom Scrolls–written as early as the late First Temple period–include the Priestly Blessing.

- Philippians 3:20; Hebrews 9:28, we eagerly look to God for the return of the Messiah, even as Israel eagerly awaited the Messiah. We also eagerly await the redemption of our bodies, Romans 8:18-25.

- Some translations may translate παρθενοις as bridesmaids. Bridesmaids had a role and function in the wedding to aid in the celebration for the couple and the guests. But virgin remains the more common translation.

- What the oil represents in the parable is somewhat vague, but most early Church fathers continued to interpret it as the service of men to God and their neighbours. Chrysostom references humanitarian acts while Augustine speaks of it as love and Arnobius the Younger as grace. This follows well with the Second Temple understanding that saw the Bible as a lamp (from Psalm 119:105; Proverbs 6:23; 4 Ezra 14:20-21; 2 Baruch 59:2) and oil as good deeds (Kohelet Rabbah 9:8; 3 Baruch 14:1-15:4).

- Mark 14:62 makes it clear that the Son of Man is a reference to Daniel 7:13 while the author of Revelation (1:7) references the same verse in declaring boldly that the Son of Man in Daniel is, indeed, Jesus the Messiah.

- In Israel, there are two distinct seasons: winter and summer–rain and no rain. The division between summer and winter is ingrained in the lives of anyone living in this land. Winter brings the rains, a mercy that falls on both the just and the unjust. But at the end of the winter comes three things: Harvest, Summer, and Salvation…or judgment. The narrative of salvation, vividly portrayed in the Biblical holidays, is intricately tied to these two seasons. All of the major holidays appointed by God in the Torah fall within just half the year, the summer, or kaitz (קיץ). This is the end, ketz (קץ), of grace to all and now either grace or judgment can come. First, God showed His salvation and judgment in Passover. Fifty days later, you have the salvation God showed at Mt. Sinai as he gives the people his instructions and guidance to live by. As summer progresses, so too does the need for God’s grace and mercy–His salvation culminates in the High Holy Days. The Festival of Trumpets, or Rosh Hashana, serves as a warning to the people. Then comes Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, where the people confess their sins. And finally comes Sukkot, the festival of booths, where God comes and dwells among His people. During this festival, the first drops of rain are expected to fall, once again showing the grace and mercy of God as His blessings are showered on both the just and the unjust, marking the onset of winter. Except, in Jeremiah God does not come to dwell with His people, for He is no longer their king–instead they worship idols. So when we see summer kaitz approaching, we see that the time of judgment is upon us as the mercies of the rainy season have ended and surely it is the time to repent.

- The first sees ‘this generation’ as referring to those people listening to Jesus at this point in the ministry of Jesus. Many of this group of people would still be alive to witness ‘all these things’ which, in this line of interpretation, refers to the ascension of Jesus and the outpouring of the Holy Spirit, plus the destruction of Jerusalem (AD 67-70). ‘All these things’, then, is not understood to include the Second Coming because to do so would imply that Jesus was mistaken about the timing of His return. The second understanding takes the view that, ‘this generation’ refers not to those alive when Jesus gave this teaching, but refers to Jewish people as a distinctive race of people. Here the word generation is used in an ethnic and not a chronological sense. This view allows one to affirm (without concluding Jesus was mistaken) that ‘all these things’ does refer, primarily, to the Second Coming of Jesus, and not just to the outpouring of the Holy Spirit and the historical destruction of Jerusalem in the first century. In this line of interpretation the teaching of Jesus is understood to be saying that the Jewish people (and the Jewish nation) will be in place to witness the Second Coming. In this case Jesus is affirming the teaching given in Jeremiah 31:35-37 that the nation of Israel will not disappear from human history. In this line of interpretation, there are many Christians who see not just the promise of the preservation of Jewish people until (and beyond) the Second Coming, but also the presence of a Jewish nation (when the Messiah returns) as being affirmed by scripture. In this case, the restoration of Israel as a nation in 1948 has huge ‘end-times’ (eschatological) implications. Thirdly, there are those who interpret ‘this generation’ as those people listening to Jesus when He gave this teaching, but interprets ‘all these things’ as a reference to the Second Coming. Therefore, one concludes that perhaps Jesus was expecting to return and to establish His Kingdom within one generation of His ascension, as we see Paul the apostle likewise consider the return of Jesus to be imminent. There is an unknown element to the nature of the return of the Messiah. Even Jesus declares that only the Father knows the day and the hour. This begs the question: how could Jesus not know because as ‘God’ He would know everything? This could be construed as a theological conundrum for Christians and it should definitely serve as a warning to anyone trying to predict the end of the age. In this thinking, it is suggested that the divine side of Jesus has voluntarily surrendered His omniscience in taking the form of a man (also explaining such verses as, “Jesus increased in wisdom and in stature”). He has done this in obedience and love of the Father. He thus urges us to keep watch in eager anticipation of His return.

- Babylonian Talmud, tractate Shabbat 153a