The Jewish Bishop and the Chinese Bible

:

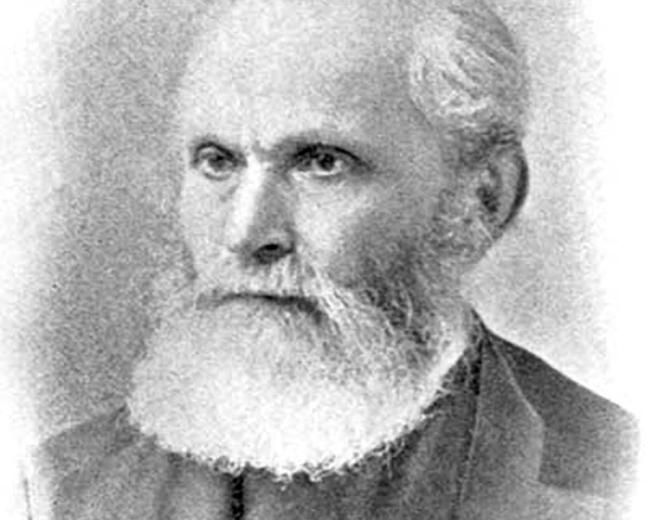

S.I.J.

Schereschewsky

(1831-1906)

Studies in Christian Mission,

Vol 22.

General Editor, Marc R. Spindler.

b

y

Irene Eber. (Brill: Leiden), 1999.

Reviewed by Theresa Newell

How

Joseph

Schereschewsky

,

a

Lithuanian Jewish

boy

,

came to be an Episcopal bishop of

Shanghai

in the 19

th

century

and the greatest Orientalist of

his day

,

and perhaps

of

all times

,

is well documented in this volume by Irene Eber.

Eber is herself an Israeli Orientalist and Louis Frieberg Professor of East Asian Studies at Jerusalem’s Hebrew University

,

E

meritus

.

The Jewish Bishop and the Chinese Bible

:

S.I.J.

Schereschewsky

(1831-1906)

Studies in Christian Mission,

Vol 22.

General Editor, Marc R. Spindler.

b

y

Irene Eber. (Brill: Leiden), 1999.

Reviewed by Theresa Newell

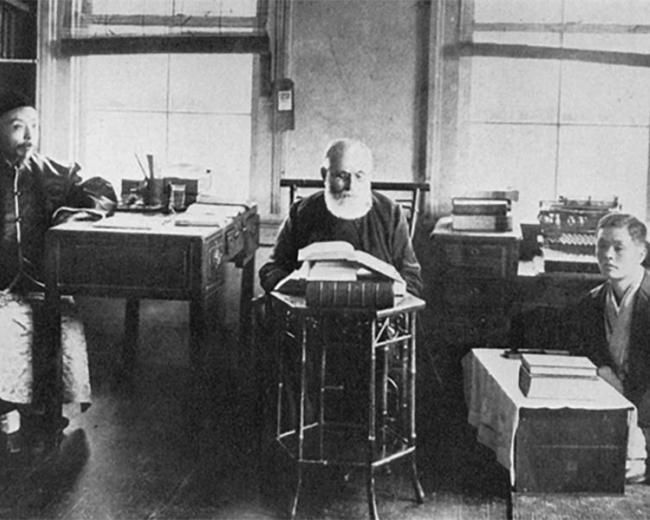

How Joseph Schereschewsky , a Lithuanian Jewish boy , came to be an Episcopal bishop of Shanghai in the 19 th century and the greatest Orientalist of his day , and perhaps of all times , is well documented in this volume by Irene Eber. Eber is herself an Israeli Orientalist and Louis Frieberg Professor of East Asian Studies at Jerusalem’s Hebrew University , E meritus .